Trade Winds 2025—Seriously and Literally

The third and final installment of my April trilogy on Trump and tariffs. This one summarizes my discussions over the past week. (If you're short on time, scroll down for the headers and graphics.)

Substack (Bastiat’s Window in particular) is loaded with intelligent, talkative, thoughtful commenters. My recent tariff pieces (“Tired of Winning, Apparently” and “Real-World Trade-Deficit Math-Magic,”) and one older one (“The Gulf of Trump”) elicited tens of thousands of page views, hundreds of comments, and dozens of emails. With few exceptions, Trump fans and foes alike offered well-reasoned, well-written, and respectful opinions.

The text below is adapted from my responses to readers at Bastiat’s Window and elsewhere.

HOW DO TRADE DEFICITS DIFFER FROM TRADE SURPLUSES?

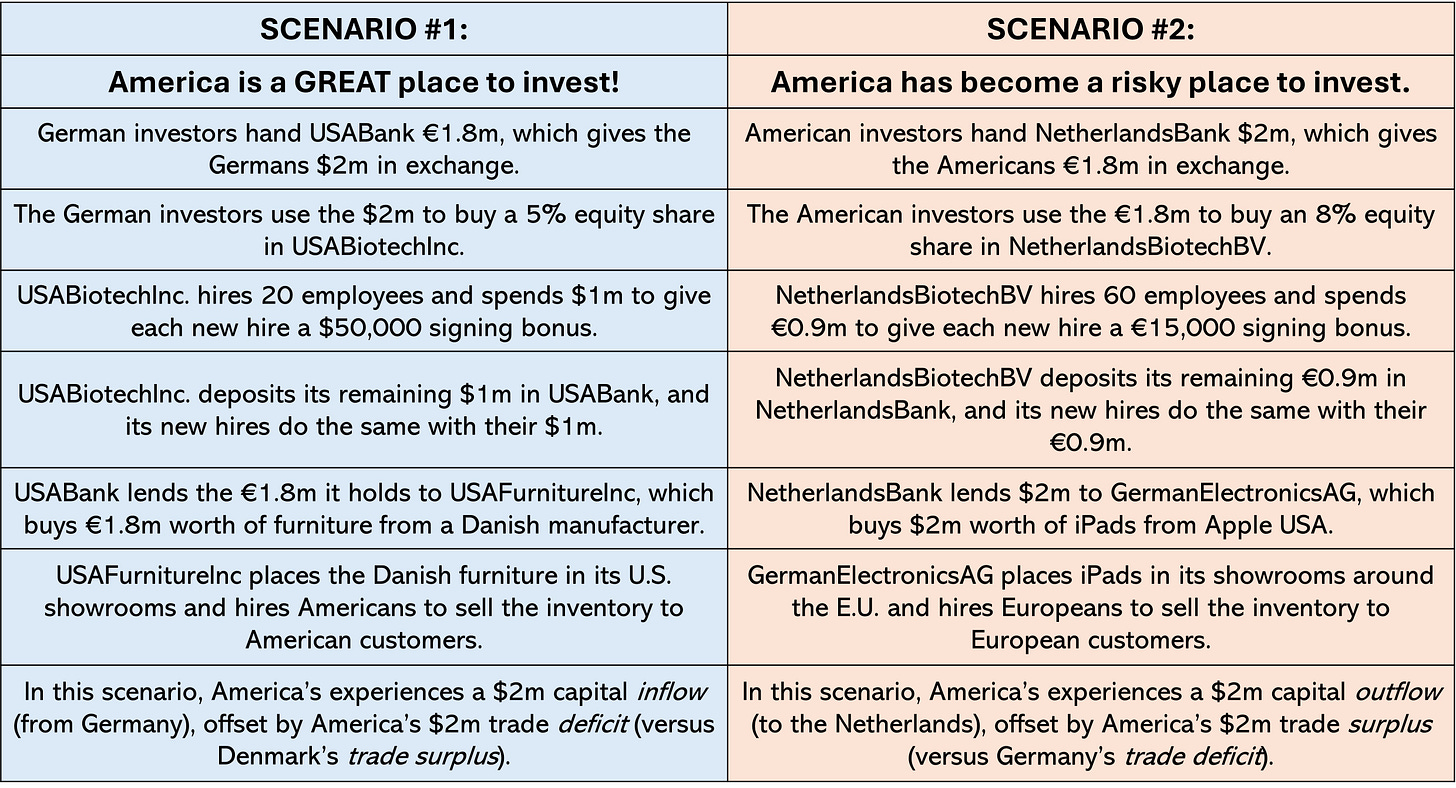

Let’s look at two hypothetical scenarios. In Scenario #1, the world views America as a wonderful place to invest. In Scenario #2, America seems risky, and investors would rather put their money elsewhere.

So, as explained in the previous post (“Real-World Trade-Deficit Math-Magic”), when the world sees America as strong and inviting to investors, we tend to run a trade deficit. When the world sees America as risky and offputting to investors, we tend to run a trade surplus. Mercantilists frown at Scenario #1, because they hate trade deficits; they smile at Scenario #2, because they love trade surpluses.

SO WHY DO PEOPLE THINK A TRADE SURPLUS IS SUPERIOR TO A TRADE DEFICIT?

Fear of trade deficits comes from atavism and tunnel vision.

The atavism is the lingering faith in mercantilism, whose medieval proponents loved the export of tangible goods and despised imports. Their economic ideal was to sell exports and accumulate idle hoards of gold. (Think of Scrooge McDuck diving into his swimming pool full of coins.) David Hume, Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and others revealed the fatal flaws in this philosophy by showing how trade is mutually beneficial for both importing and exporting countries. Imported goods bring both satisfaction to consumers and inputs with which investors can generate future wealth. Because of this latter factor, there’s no limit to how long a nation can run a trade deficit.

The tunnel vision is the tendency to focus on narrow segments of the economy and ignore the rest. In the deficit/surplus example above, mercantilist nostalgia might—pun intended—pine for the loss of some furniture-making factories in America and long for them to come back. But mercantilism (currently traveling under the moniker of “anti-globalism”) ignores the other parts of the story. In the example above, mercantilists remember bygone American furniture factories but fail to notice the willingness of foreigners to invest in America, the rise of new American industries like biotech, the high-paying jobs these new industries bring, the wealth those new industries create as their newly wealthy employees buy furniture and cars and healthcare, and the capacity of Americans to consume and invest in magnitudes unimaginable to their parents or grandparents.

As seen in the accounting equations in the previous post (“Real-World Trade-Deficit Math-Magic,”), you can’t get rid of a trade deficit without also losing foreign investments in America. This insight was undiscovered in the age of mercantilism and unappreciated in the age of “anti-globalism.”

AREN’T THOSE EQUATIONS JUST ACADEMIC THEORY?

Nope, they’re accounting identities that simply apply the logic and discipline of double-entry bookkeeping to entire economies. The equations don’t say “tariffs are bad” or “tariffs are good” or preclude the possibility that a tariff could boost national income. They don’t offer any opinion on whether trade surpluses are better than trade deficits (or vice versa). But, they do force tariff proponents to reveal and justify their assumptions as to how tariffs generate wealth. As the “Math-Magic” essay suggests, those assumptions tend to be far-fetched (e.g., tax increases don’t affect people’s consumption or saving), and historical examples of tariffs boosting national income are few to non-existent.

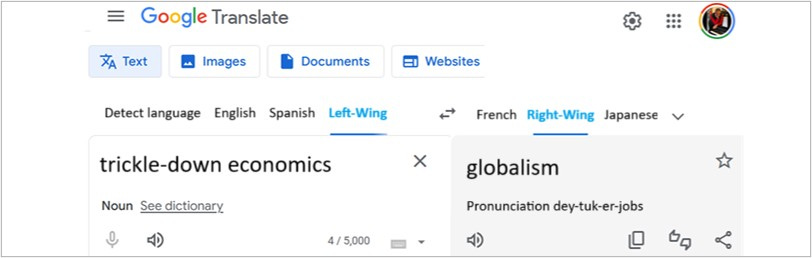

WHAT IS GLOBALISM?

“Globalism” (a.k.a., free trade) is to those on the political right what “trickle-down economics” (a.k.a., free markets) is to those on the political left. Both are vacuous pejoratives that translate loosely into English as, “Somewhere on Earth, buyers and sellers are engaging in voluntary trade and minding their own business AND WE HAVE TO STOP THEM.”

DOES A TRADE DEFICIT MEAN WE’RE BEING RIPPED OFF?

Mercantilists (a.k.a., Economic Nationalists), like Socialists, often presume that a voluntary financial transaction necessarily creates a winner and a loser. From the 1700s on, coherent economic analysis dispelled such nonsense by refining the concept of mutually beneficial trade and documenting its validity. In the deficit/surplus example above, followers of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders alike might well see an American company’s purchase of Danish furniture as “Americans lose, Danes win”—followed by demands to discourage such purchases by way of tariffs. By the same token, Economic Nationalists and Socialists in Europe might well see Europeans’ purchases of iPads as “Americans win, Europeans lose”—with equivalent demands for tariffs to raise the price of iPads for Europeans. But 250 years of theory and observation tell a very different story—tariffs and other trade barriers harm both sides of a transaction.

BUT HASN’T XI JINPING MADE CHINA RICH BY IMPOSING TARIFFS AND OTHER TRADE BARRIERS?

Numerous readers see China’s Xi Jinping as some Trade War Mastermind, using tariffs to enrich China at America’s expense. In fact, his tariffs damage China’s economy as much as Trump’s tariffs damage America’s economy. China’s incredible growth is happening in spite of Chinese tariffs, not because of them. Xi’s Secret Economic Weapon is simply the fact that he and his government are not nearly as self-destructive and economically illiterate as were China’s rulers 1371 till 1976.

For many centuries, China was Earth's greatest economy, and the Chinese were Earth's richest people. Then, in 1371, the Emperor Hongwu decided (in contemporary terms) to End Globalism and Make China Great Again. Foreign trade was deemed to be corrupting and damaging to Chinese commercial interests, so the emperor issued the first of a long series of “sea-bans” (haijin). Private foreign trade was banned, with violations punishable by death (plus the offender’s family and neighbors would be exiled from their homes). The result was to turn China into a gigantic compost pile of endless poverty and suffering. In 1949, Mao Zedong’s Communists conquered China and decided that 578 years of ruination wasn’t nearly enough; they snuffed out what few vestiges of rational economic behavior remained, leading to decades of starvation and killing.

When Mao died (1976), the average American earned around 30 times as much as the average resident of China. Under a succession of post-Mao leaders, China began edging away from Communism. By 2001, the average American earned around 10 times as much as the average Chinese person—in relative terms, a huge improvement for the still-dirt-poor Chinese. In the years since (including Xi’s presidency, which began in 2013), the government continued throwing off even more Communist shackles, so today the average American only earns three or four times as much as the average Chinese person. Chinese people would be doing better without the tariffs and and other impediments to trade, but give Xi credit for not wrecking his country as badly as Hongwu, Mao, or the six centuries of isolationists between. Xi’s trade bureaucrats are less than ideal, but a huge step up from Hongwu’s eunuchs and Mao’s Gang of Four.

NOTE: Estimates of the ratio of American-to-Chinese wealth vary somewhat, depending on the data uses. But 30, 10, and 3 or 4 are close enough.

BUT IF ANOTHER COUNTRY, LIKE CHINA, IMPOSES TARIFFS AND OTHER TRADE BARRIERS, SHOULDN’T WE REACT IN KIND?

A tariffs-bring-wealth reader at another website said, (1) China is laughing at us; (2) China’s has grown rapidly since 2001 AND has implemented tariffs and other trade barriers during that time; and concluded (3) Therefore the U.S. should imitate China by implementing tariffs and other trade barriers. My response (edited here) was:

“Imagine two high school friends, class of 1980. John, a teetotaler, went to law school. In 2001, he was earning $200,000 and now earns $250,000. Randy started using heroin after graduation, lived in his Mom’s basement, and earned $10,000 a year wiping windshields of cars stopped at red lights. In 2001, he gave up heroin and started drinking a fifth of bourbon each day. After switching from heroin to bourbon, he got a job dressing up as Uncle Sam and twirling a large red arrow in front of a used-car dealership and now earns $30,000 a year. By your logic, John should look at this and say, ‘Randy’s income has TRIPLED since he started drinking. I’m going to start drinking a fifth a day so MY salary will triple like Randy’s.’”

Here’s another of my metaphors for the logic of trade wars:

“China says, ‘Our government will use sledgehammers to break the hands of 90% of China’s people to discourage them from buying American gloves.’ America responds with, ‘Oh YEAH??? Then OUR government will use sledgehammers to break the feet of 90% of AMERICANS to discourage them from buying Chinese shoes.’ China’s tariffs are self-destructive, and America’s retaliatory tariffs are equally self-destructive.”

WELL, IF TARIFFS AND OTHER TRADE BARRIERS ARE SELF-DESTRUCTIVE, WHY DO SO MANY COUNTRIES ENACT THEM?

I can suggest four less-than-admirable reasons:

IGNORANCE: Some economic nationalists sincerely believe that mercantilism generates wealth.

CRONYISM: Politicians often use trade barriers to benefit favored political groups (e.g., steel industry, farmers) at the expense of everyone else.

SELF-AGGRANDIZEMENT: Trade barriers provide employment, prestige, power, and international junkets to those who set and administer the barriers.

QUIXOTISM: Some see true tit-for-tat reciprocal tariffs as a way of inducing other countries to lower tariffs. The logic is coherent, but the incidence of success is vanishingly small.

I’ll add that in certain times and places, tariffs have served a legitimate role as revenue-raising mechanisms. Tariffs were essential to funding the federal government in the 19th century because an income tax was not yet constitutionally permissible and because the predominance of cash transactions and the paucity of record-keeping would have made it wholly impractical for a proto-IRS to tax income back then. Tariffs were economically destructive and tariff-collection was notoriously corrupt, but 150 years ago, the federal government lacked good revenue-raising alternatives. (In my days in international banking, a number of Sub-Saharan African countries relied on tariffs for these same reasons.)

TARIFFS ARE JUST A FORM OF SALES TAX, AND LOTS OF ECONOMISTS LIKE CONSUMPTION TAXES. WHAT GIVES?

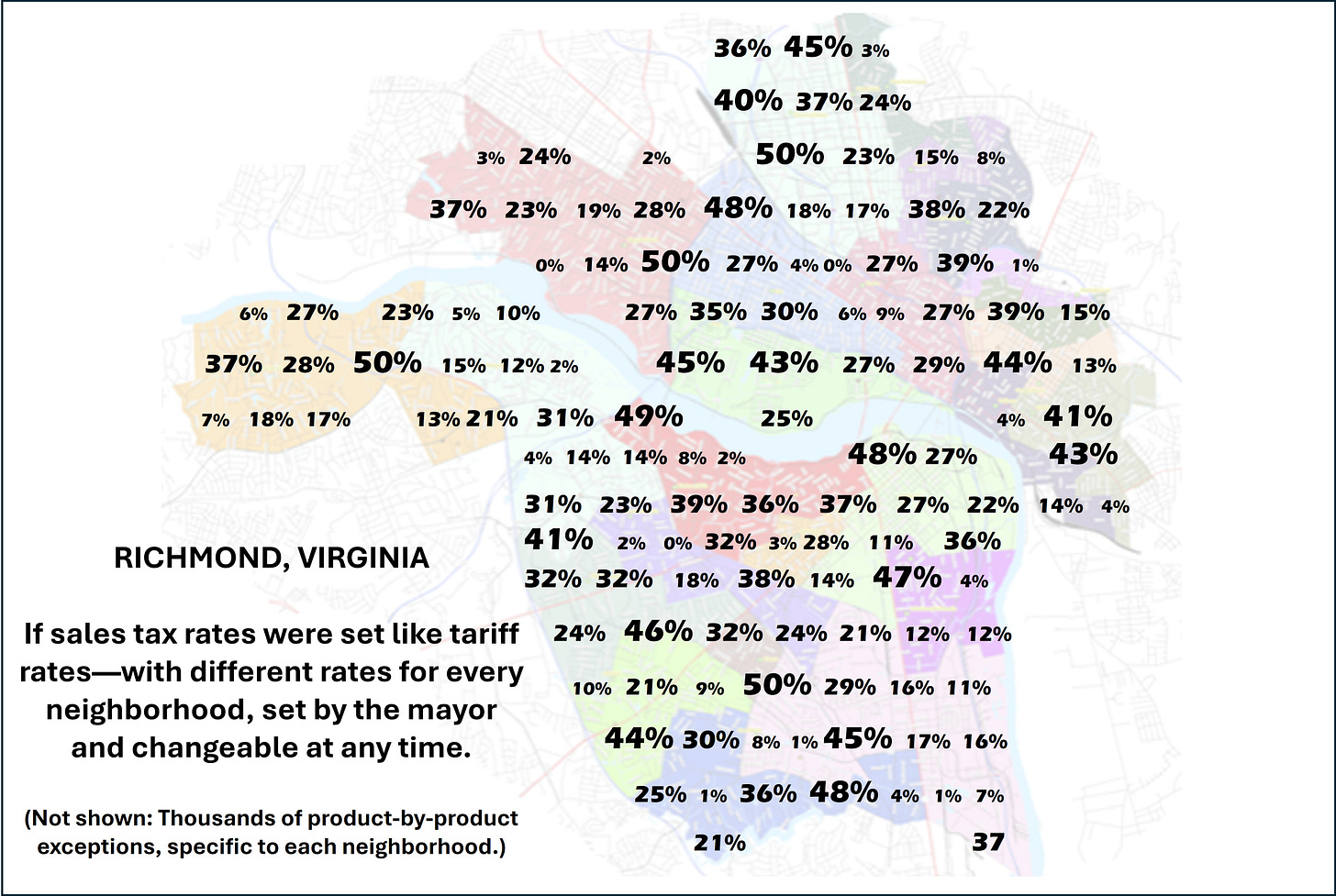

Excellent point, but sales taxes are generally low, uniform, slow-to-change, and subject to legislative deliberation. In contrast, tariffs can be huge, volatile, and arbitrary. In the 1960s and 1970s, Congress foolishly surrendered its powers over tariffs, giving presidents authoritarian control over tariff rates. To understand how tariffs differ from sales taxes in America, imagine that Richmond, Virginia, empowered its mayor to set sales tax rates as the president sets tariff rates—without any need for approval from City Council or anyone else.

One morning, the mayor says that merchants in the Fan District are “ripping us off,” so he announces that Fan District sales taxes will henceforth be 25%. In his ire against the Fan District, he also decides to impose rates of 42% in the Museum District, 12% in Scott’s Addition, 47% in Church Hill, 34% in Shockoe Bottom, and on and on through 150 other neighborhoods. Except that sales taxes on electronic devices in Church Hill will be 24%, the tax on food in Shockoe Bottom will be 12%, and so on with other special exceptions. Then, after merchants go ballistic, the mayor announces that for the next 90 days, the sales tax in Fan District will be 125% (except for consumer electronics, which will be 15%) and the tax rates everywhere else will be 10%. During that 90 days, the mayor will meet with representatives from each of the 150 neighborhoods and carve out separate deals with each of them. Some neighborhoods complain that they had already signed deals with this mayor, but that he has now torn up all of those deals. Meanwhile, the city’s Sales Tax Department will send agents all over town to check up on each merchant’s compliance.

Loads of commenters cited President Trump’s wheeler-dealer negotiating skills and his unpredictability as America’s greatest advantage in this controversy. The counterargument (to which I subscribe) is that this wheeler-dealer bit is the biggest negative of President Trump’s taxtariff policies—that it forces businesses to base their plans on their short- and long-term forecasts of one man’s opinions and changes of mind. As I noted in the preceding post, Democrats ought to maintain some modesty in this matter, as it was Democratic-run Congresses that handed presidents this fearsome power, and it was mostly Democrats who built the case for tariffs between World War II’s end and Donald Trump’s beginning.

By the way, this map also sheds light on the Great Depression. As I explained recently, the Roaring Twenties likely resulted from the desire of Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge to keep their hands off of businesses to avoid destabilizing them; in contrast, Herbert Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt were both dealmaking busybodies who constantly interfered in markets, changing the rules of the game over and over until business crawled into a shell for more than a decade.

SHOULD YOU TAKE TRUMP SERIOUSLY, BUT NOT LITERALLY?

Several readers said I should take Trump seriously, but not literally—which was journalist Selena Zito’s famous take on candidate Trump in 2016. Zito’s perception was razor-sharp, but my responses were threefold:

“Seriously, but not literally” had its charms for an insurgent candidate but is untenable for a sitting president who has the nuclear codes and the power to vastly alter the conditions of world trade on whim—nation by nation, product by product, day by day.

World markets clearly take him literally, even if his supporters don’t.

Trump supporters who traffic today in this idea that the president does not mean what he says do no service to their world, country, president, party, or selves.

I was told once that I should not take Trump's tariffs literally. I said they were written down as executive orders. If I can't take written executive orders literally, the word has lost all meaning.

What happens in your view when China invades a country that no longer produces steel?

And China threatens all other steel-producing countries not to sell you any steel?